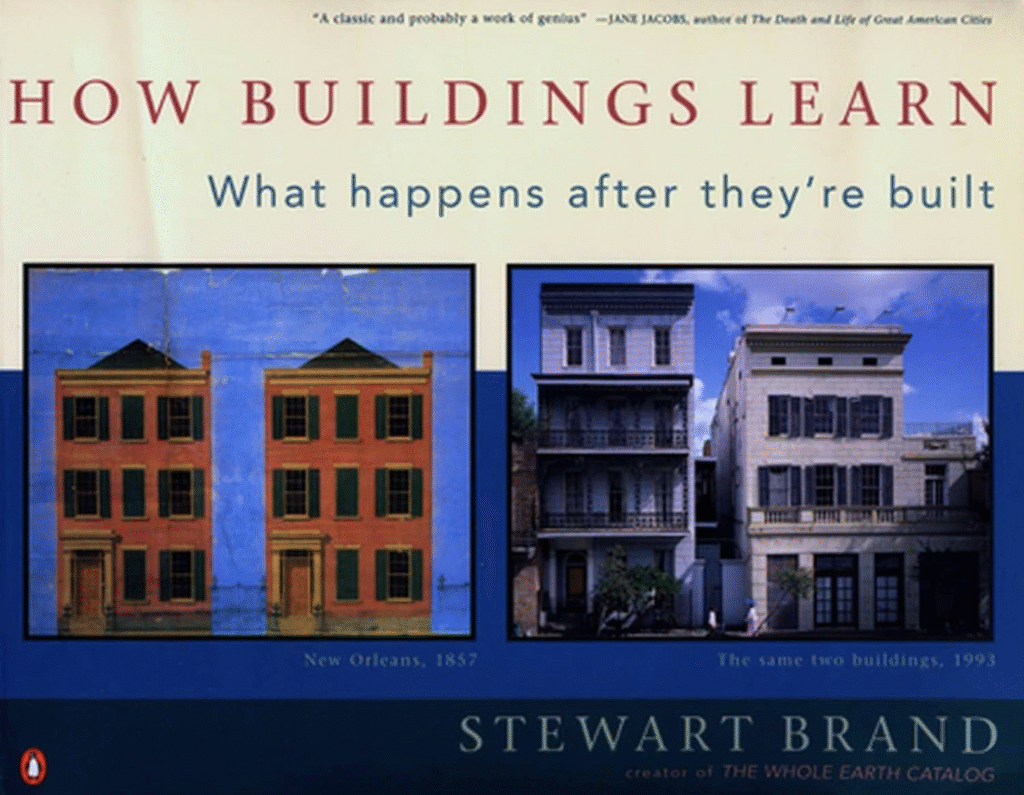

HOW BUILDINGS LEARN

(Source www.amazon.com)

Stewart Brand (1938-) is an American project developer and author. He studied biology at Stanford University, and served in the army as an infantry officer. Later he studied design, photography, and participated in a scientific study of then-legal LSD. Since 1982, he has been living in a working 20m long tugboat with his wife.

He has founded, cofounded, organized and coorganized many diverse projects, some of which are as follows: He was the founder and publisher of the original Whole Earth Catalog which Steve Jobs likened to a paperback version of Google 35 years before Google itself came along. In 1973, he designed and organized ‘The New Games Tournament’. Brand co-organized the first Hackers Conference in 1984. In 1988 he cofounded the Global Business Network. He is the president of the Long Now Foundation which has Brian Eno as a board of director. A sagittarius. How Buildings Learn was published in 1994.

Buildings are mostly perceived as static constructs since it is not easy to perceive at once the changes they go through over the years. Brand explores this overlooked time dimension of buildings. Thinking of them as merely artworks that can be finished, or commodities that need to be laced with fashion, and therefore trying to conceal ‘the mess’ they actually are, steers us from their reality. ‘The word ‘building’ contains the double reality. It means both ‘the action of the verb ‘build’’ and ‘that which is built’- both verb and noun, both the action and the result. Whereas ‘architecture’ may strive to be permanent, a ‘building’ is always building and rebuilding. The idea is crystalline, the fact fluid. Could the idea be revised to match the fact?’

Brand says no building adapts well- they are designed, budgeted, financed, constructed, maintained, taxed and regulated not to; but they adapt anyway, however poorly because the usages in and around them constantly change. Aging is a valued quality in buildings, but decay is considered too much and deathly, and new buildings get forced to ripen quickly. ‘Over 50 years, the changes within a building cost three times more than the original building’.

Brand defines six layers of a building: Site- is almost eternal. Structure- lasts around 30 to 300 years. Skin- lasts around 20 years. Services- wear out or obsolece every 7 to 15 years. Space Plan- can change every 3 years or so, but exceptionally quiet houses may last around 30 years. Stuff- frequently. ‘Because of the different rates of change of its components, a building is always tearing itself apart’. The quicker components provide originality and challenge, and the slow ones provide continuity and constraint.

(Soruce: www.wikipedia.org)

While all buildings change with time, only some improve. ‘Age plus adaptability is what makes a building come to be loved’. Brand defines two separate types of buildings: ‘The Low Road’ is the low-rent, styleless, high-turnover type of building where a lot of creativity easily takes place because of the freedom it provides. ‘The High Road’ buildings receive continuous care over time, have enormous character of their own. ‘These are precisely the two principal strategies of biological populations- the opportunist vs. the preserver’- dandelions and oaks. Yet he says; most buildings have no road virtues- bashing the fashionable architecture: When clothing goes out of fashion, you can discard it, but with a building, it is ‘months of glory, years of shame’. And he finds the culprit in architectural photography which is used often now to decide the value of a building which totally disregards the time dimension of building. (I would like to add ‘context’ in a broad sense, and give the example of Niemeyer’s Niteroi Art Museum, which also does photograph well, but the wind created underneath it by its structure on a scorching hot Brazilian day is not capturable by photography).

He says we need to honor buildings that are loved, rather than merely admired: Admiration is from a distance, love is up close and cumulative. ‘Every building leads three contradictory lives- as habitat, as property and as a component of the surrounding community’. And the lesson of realty laced with reality is really: ‘Get rich slow’.

To ensure a building’s longevity, protect it from markets and water, and feed it money- but too much of it disrupts its continuity and integrity and too little of it may cause irreversible decay. Solid construction that would require little maintenance is often expensive, and preventive maintenance is boring, so both are unpopular, Brand says. To this I would like to add that even inexpensive measures that architects propose to diminish later maintenance needs are usually viewed as redundant- in the excitement and heat (and expense) of building, they seem as concerns of a too distant future.

‘The romance of maintenance is that it has none. Its joys are quite ones. There is a certain high calling in the steady tending to a ship, to a garden, to a building. One is participating physically in a deep, long life’.

Brand quotes Sim van der Ryn: ’Everyone who can afford it wants their home to be a nightclub big enough to entertain and impress everybody they know.’ Also saying that this extrovert fantasy about ‘home’ often collides with the introvert reality of home which needs to provide the familiar, the comfortable sanctuary.

Talking about ecopoiesis, the process of a system making a home for itself, Brand says the dwellers and the dwelling need to shape and reshape themselves to each other, until there is a tolerable fit. This requires time and money which are seldom taken into account.

System theorist Herbert Simon’s coined term ‘satisficing’ (a combination of satisfying and suffering) refers to reducing problems just enough as opposed to fully solving them or optimizing thoroughly- ‘It is precisely how evolution and adaptation operate in nature’. Brand says you cannot predict or control adaptivity, you can only make room for it.

‘Programming’ is largely about taking into consideration the immediate occupants of a building; however using only this information excludes the probable collection of future users/uses of the building and becomes near-sighted: ‘The more adapted an organism to present conditions, the less adaptable it can be to unknown future conditions’. ‘Scenario planning’ on the other hand, focuses on a deeper future, embracing diverse possibilities. ‘The trick is to frame the building question in a larger context, so instead of leaping to ‘We need a bigger building’, really explore the more general problem, ‘We need to handle our growth’’; similar in analogy to historical preservation- a future preservation.

‘A building is not something you finish, it is something you start’. And building users need to be involved in the evolving of it, as well as accustomed to doing its maintenance, instead of being its passive victims. And architects need to step from being only artists of space to artists of time. Post-occupancy evaluation is also invaluable in this regard, as well as in better scenario developing. And obviously understanding that, spacing out the design and construction work over time is a healthier approach- rather than focusing on creating one ‘perfect’ edifice for photographing that will soon be not so ‘perfect’. As in ‘Ways of Being’, a building is a ‘living’ thing as Brand demonstrates in his book, and you can dress the baby all you like, but if proper care is not taken, and healthy interaction is not allowed, malfunctions will arise. What matures authentically over time is not replicable by means that override time, although attempts are forever made.

The ‘beingness’ and time dimension of architecture do not escape decent architects, yet as architects are forced to adapt to market expectations, a monologue is not healthy, and books such as these are invaluable for a dialogue instead.

‘How do people learn to do cheap problem-prevention instead of expensive problem-cure? There’s no immediate reward for putting in a sprinkler system, only extra nuisance and expense. A larger, slower entity- the community- has to do the learning, and instill the lesson, by convention, habit, rite or law’.

‘There is no art as impermanent as architecture. All that solid brick and stone mean nothing. Concrete is as evanescent as air. The monuments of our civilization stand, usually, on negotiable real estate; their value goes down as land value goes up.’

Ada Louise Huxtable

‘The romance of maintenance is that it has none. Its joys are quite ones. There is a certain high calling in the steady tending to a ship, to a garden, to a building. One is participating physically in a deep, long life’.

‘To change is to lose identity; yet to change is to be alive. Buildings partially resolve the paradox by offering the hierarchy of pace- you can fiddle with the Stuff and Space plan all you want while the Structure and Site remain solid and reliable’.

‘Evolution is always away from known problems rather than toward imagined goals. It doesn’t seek to maximize theoretical fitness; it minimizes experienced unfitness.’ ‘That’s why evolutionary forms such as vernacular building types always work better than visionary designs such as geodesic domes. They grow from experience rather than from somebody’s forehead.’

Author: Stewart Brand

Title: How Buildings Learn / What Happens After They’re Built

Published: 1995, by the Penguin Group

First published: 1994

Pages: 243