MARCEL DUCHAMP

(Source: www.amazon.com.tr)

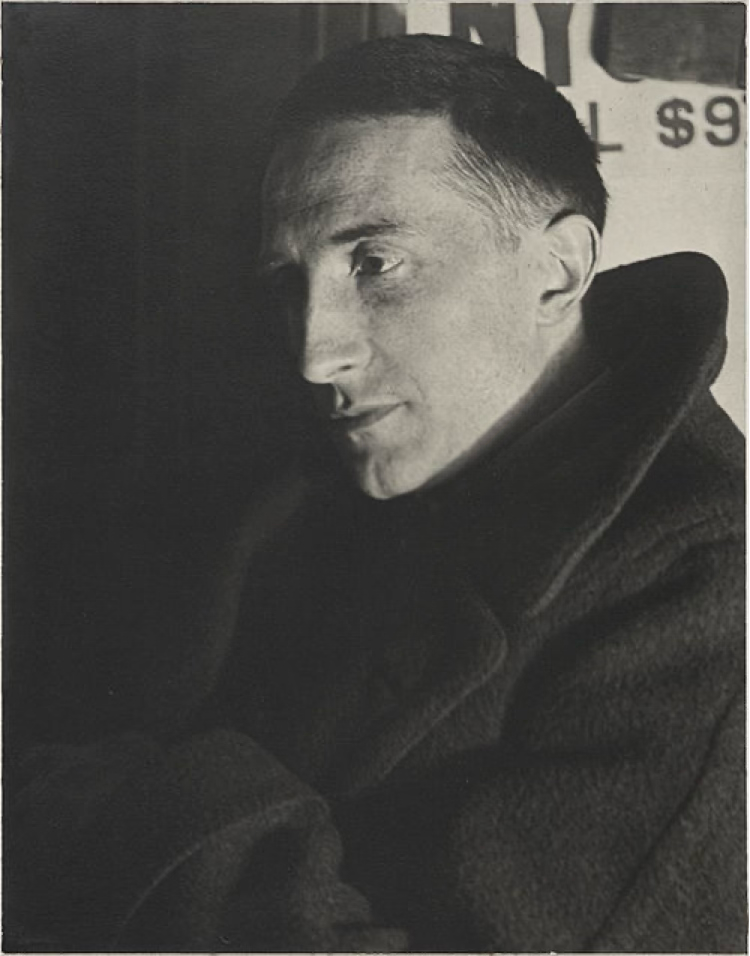

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) was a French painter, ‘sculptor’, ‘anti-artist’, chess player and writer whose influence contributed to the developments in Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism and conceptual arts. The original book was published in 1959. Design and layout was by Duchamp and A. Fawens, text was compiled by R.Lebel after 10 years of observations and interviews, including essays by A.Breton, H.P.Roche and Duchamp. This is a 2021 facsimile of the 1959 English edition with supplements.

According to Duchamp, his father was a kindly and indulgent father. ‘Of his mother Duchamp today remembers above all her placidity, even her indifference, which seems rather to have hurt him until it became a goal for him in his turn to attain’.

His maternal grandfather, a shipping agent, also painted and did printmaking. Duchamp’s notary father supported him financially all his life, as well as his five other kids. Gaston, Raymond, Marcel and Suzanne all went on to have art careers.

Lebel says the bourgeois father did not see this as a catastrophe for ‘the time would soon come when [bourgeoise] would annex modern art as a part of its system, for it was obvious that it was running a great risk if it continued to let the artist develop as a stranger, and consequently as an enemy’.

His revolutionary ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ was painted in 1912. Chronologically close influences were his friendship with F.Picabia with whom he shared the sarcastic spirit, A. Jarry’s work and his pataphysics, Duchamp’s attending of a R.Roussel performance, the rise of Cubism and cinema, and the 1909 Futurist Manifesto. The work introduced movement to the static Cubism of the time, a new way of presenting the classic nude usually either standing or reclining, mocked the Futurist’s forwards and upwards drive with its ‘descending’, and it employed an odd humor which was embraced by the writers of the time, but not yet by the painters of the time. The work created a scandal, and he was asked to take it down, to which he obliged.

Duchamp withdrew more and more into isolation, and started devoting himself to theoretical considerations. The Nude gained him recognition in the US exhibition of European Artists, the Armory Show in 1913.

Duchamp had started working on his first mechanical instruments as he no longer wanted to focus on a retinal aesthetic, and his protest against the excessive importance attached to some works of art also materialized in his readymades. Lebel says he spoilt the fun, but also created alternative fun.

‘But is the intention to reduce everything to the same level of complete equality? Certainly not, for even it depends upon a choice which is the source of its very existence’.

With the outbreak of war, he soon left to live in the US. In 1915, he started on the ‘Large Glass’ which he worked on for 8 years, finally abondoning it unfinished. ‘The design of the Glass [can] never be seen by itself, apart from its surroundings, [ceaselessly] transformed by a background of reflection in which that of the spectator himself is included.’ In a way, he has turned the background into a ready-made continually in motion. To Cabenne D., Duchamp said when asked if his Large Glass is a negation of woman: ‘It’s above all a negation of woman in the social sense of the word, that is to say, the woman-wife, the mother, the children, etc. I carefully avoided that, until I was 67. Then I married a woman who, because of her age, couldn’t have children.’ As Duchamp likes to provoke others, and contradict himself, this may be something he made up on the spur of the moment, but he did indeed only have a brief marriage when he was young, and married again in 1954, and had no children as the rest of his siblings.

(Source: www.wikipedia.org)

The famous urinal ‘The Fountain’ that he sent to an exhibition he was co-founder of, in 1917, was rejected. (There is speculation that the work was sent by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, or that it was her idea, but that discussion would open pandora’s box, as there is also in immediate vicinity Roussel and Jarry’s influence which already raise the eyebrows to politely ask where an artist begins and ends, or more directly, define plagiarism).

In 1915, he painted his last painting, Tu m’. From then on, he started living mostly in France and the US in alternating periods. Duchamp mostly renounced all creative activity before the age of 40, and concentrated mostly on chess, a former family activity of his, although he kept contact with the art circles socially as well as contributing theoretically/conceptually. In 1932 he published a treatise on chess with Halberstadt, producing a formula for the bishop and knight mate. He also devised a martingale strategy he used at the roulette tables at Monte Carlo where his definition of success was neither to win nor to lose.

His Box-in-a-Suitcase is a portable museum of most of his work in miniature form which critics have attributed a myriad of interpretations to, and I also think it is potent in that sense, yet I mostly see it as the tired, sarcastic and playful eyebrows of a person who lugged suitcases all his life. ‘Characteristically, one year before the war Duchamp foresaw that he must pack his bags in as small a space as possible.’ A limited edition of it was done by him between 1938 and 1941.

With the three boxes he compiled of his notes, drawings and photographs, which were intended as companion to his works, mostly to the Large Glass, he seems to have attempted to remove the focus on the retinal quality of the work, and shift it to the realm of the mind. In Locus Solus, Roussel first describes his enigmatic constructs plainly, then supplies stifling information that removes all mystery, and he also published a book explaining his writing process. Duchamp goes through similar motions, yet we are not really demystified in the end. He rides the thin line between being an obnoxious, sarcastic, mean narcissist artist and being a playful inspirational wise artist. It is stressed over and over again in the book how much he valued his own freedom, and respected others’.

In 1942 Duchamp organized the Surrealist Exhibition in New York with Breton, also later organizing the 1947 Surrealist Exhibition in Paris with him again. He produced sculptures and ready-mades sporadically over the years, also exhibiting infrequently: ‘It is typical of Duchamp that the least effort is enough to prevent his ever being forgotten. He lets others do the work, and he inspires others rather than acts himself. That is why, in the fullest sense of the word, he is a ringleader.’

In his 1957 statement in Houston (which Duchamp describes as ‘three circus days [where] I played my role of artistic clown as well as I could’), he insists on the spectator’s active participation in the creative act, which Lebel interprets as Duchamp having completed the cycle by contradicting himself.

He created such an air of mystery around his works that people even wondered if he were practising alchemy to which he replied: ‘If I have practised alchemy, it was in the only way it can be done now, that is to say without knowing it’. Duchamp seems to have not cared much about being misunderstood, or misleading critics, but he has also said: ‘True art criticism should be a contribution and not as it is in most cases, a simple translation of what is untranslatable’.

Breton’s essay in the book, mentions Poe’s thinking on originality as rather being achieved by a spirit of negation, rather than by a spirit of invention. Duchamp does not stop at negation: ‘If we give the attributes of a medium to the artist, we must then deny him the state of consciousness on the esthetic plane about what he is doing or why he is doing it’- keeping in mind he said this in the spirit of an ‘artistic clown’.

Harriet and Sidney Janis on Duchamp: ‘He swings like a pendulum between the inertia-acceptance of reality and suicide-refusal, which gives him his dynamism’.

Lebel: ‘Duchamp’s work as a whole can be seen as a chessboard on which each pawn occupies a strategic position. This explains the rarity of the moves and the impossibility of repetition’. Lebel compares Rimbaud and Duchamp, saying that the former’s later life contradicted his work, whereas Duchamp’s life carried ‘to the ultimate consequences a resolution he reached when he was only 25 years of age’. A constricting criteria imposed on artists which I believe is at least partially relieved by humor, contradiction, irony, indifference, and a mysterious air Duchamp created around himself and his work. Periods of intense work could produce sincere work (and can also produce strong work), whereas shouldering the weight of a lifelong struggle, on many occasions, show the employment of deception to keep up appearances- but what is not deception, and to each their own.

Duchamp: ‘The work of art is always based on the two poles of the onlooker and the maker, and the spark that comes from that bipolar action gives birth to something- like electricity. But the onlooker has the last word, and it is always posterity that makes the masterpiece. The artist should not concern himself with this, because it has nothing to do with him’. A leo.

‘[From] now on the bourgeoise was to object less and less to its children’s chosen calling, for they would become its ambassadors to art as if to new lands to be colonized and would (most often unconsciously) make certain that the new monopoly would be added to those it already held in industry, commerce, finance, literature and education. By this conquest perhaps the most formidable of the internal enemies who stood in the way of bourgeois domination, the artist as outlaw, would be suppressed.’

‘To all appearances, the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing. If we give the attributes of a medium to the artist, we must then deny him the state of consciousness on the aesthetic plane about what he is doing or why he is doing it. All his decisions in the artistic execution of the work rest with pure intuition and cannot be translated into a self-analysis, spoken or written, or even thought out.’

‘[Art] may be bad, good or indifferent, but, whatever adjective is used, we must call it out, and bad art is still art in the same way that a bad emotion is still an emotion.’

Author: Text by: Robert Lebel- chapters by Marcel Duchamp, Andre Breton and H. P. Roche, design and layout by Marcel Duchamp and Arnold Fawcus

Supplement book edited by Jean-Jacques Lebel and Association Marcel Duchamp

Translator: George Heard Hamilton

Title: Marcel Duchamp

Published: 2021, by Hauser & Wirth Publishers

First published: 1959 (in French, titled Sur Marcel Duchamp)

Pages: 192, supplement book: 56 pages