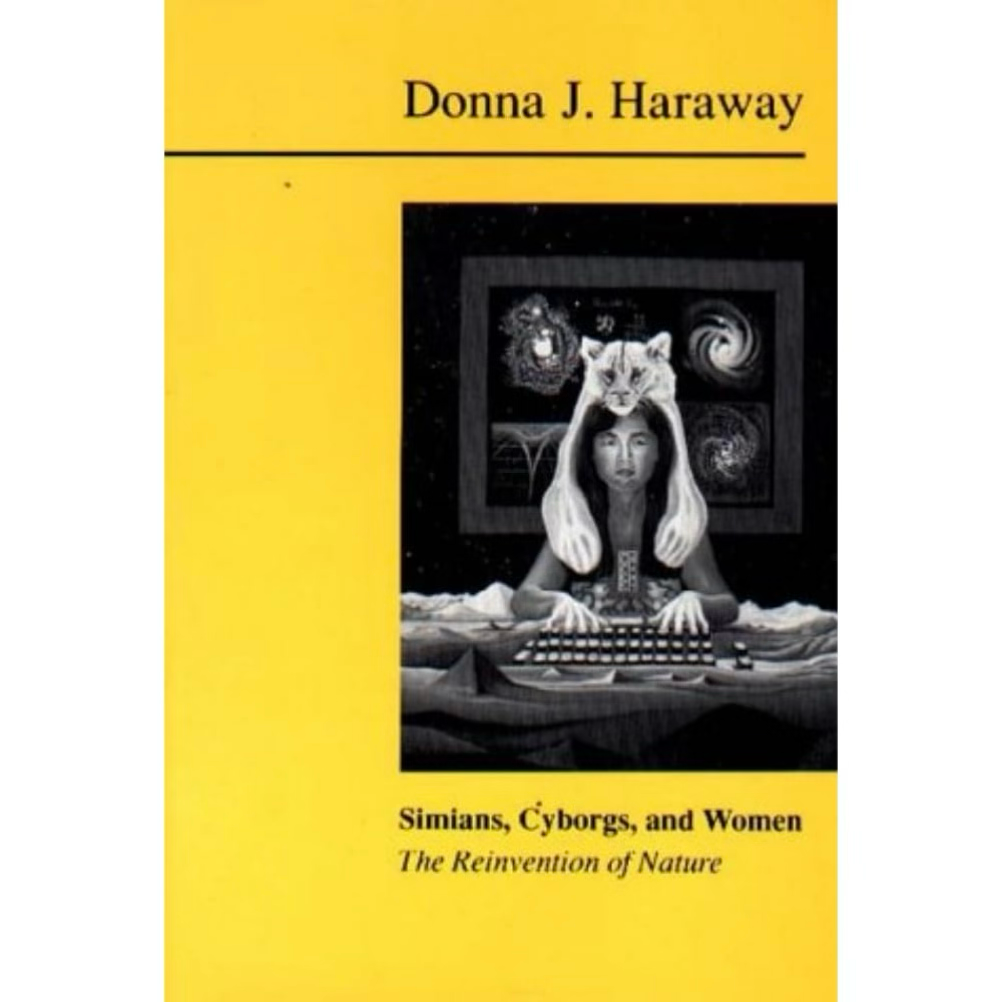

SIMIANS, CYBORGS AND WOMEN

(Source: www.amazon.com)

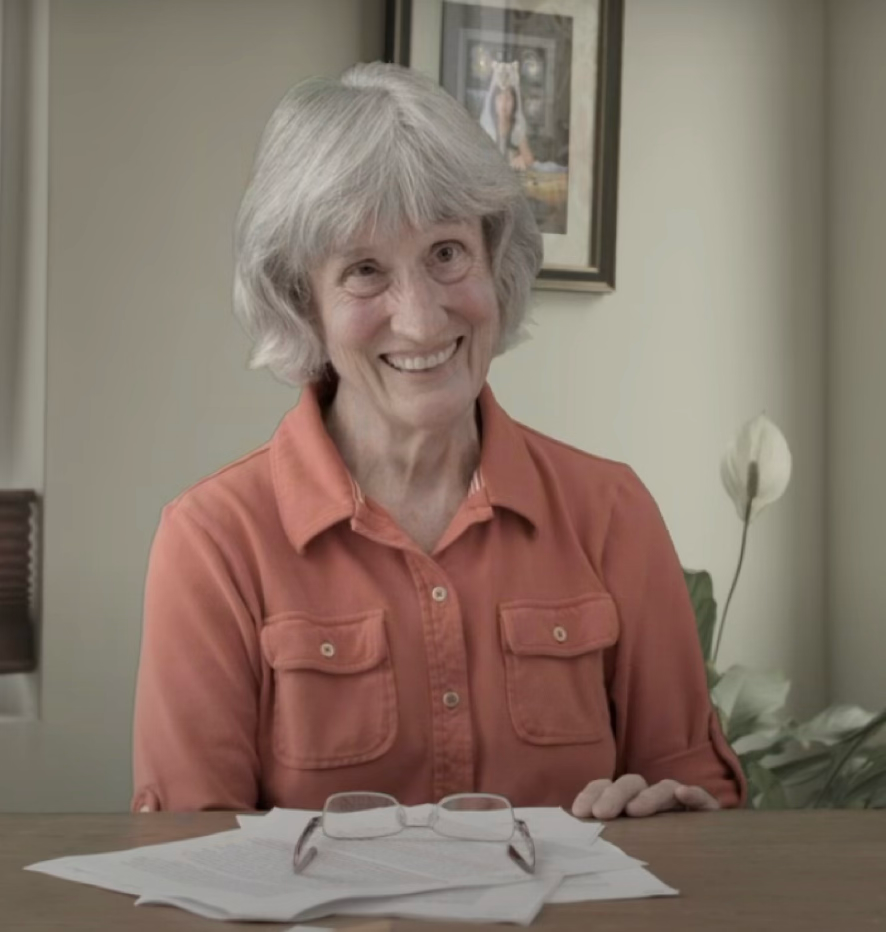

Donna Haraway (1944- ) is an American scholar and author known for her contributions in the fields of feminist theory, animal, science and technology studies. She was taught by Catholic nuns in her earlier life. She majored in zoology, and studied evolutionary philosophy and theology before receiving her PhD at Yale University. Her dissertation was about the use of metaphor in shaping experiments in experimental biology which in edited form became her book ‘Crystals, Fabrics and

Fields: Metaphors of Organicism in 20th Century Developmental Biology’.

Haraway taught history of science and women’s studies at the University of Hawaii between 1971 and 1974, then at Johns Hopkins University between 1974 and 1980. She is a professor emerita in the history of consciousness and feminist studies departments at the University of California, Santa Cruz where she started working in 1980.

A virgo.

Simians, Cyborgs and Women/ The Reinvention of Nature was compiled from her essays written between 1978-1989, and was published in 1991. The underlying current in all is about how to exist in a world riddled with constructs/dominations of race, colonialism, class, gender and sexuality.

Part 1 examines the scientific constructs created in the various studies of primates, and its effects on feminist struggles. One suggestion Haraway makes is, how animals live and relate to their environments may have little to do with us.

Quoting R.M.Yerkes and his work in eugenics and primatology, she points that his aim was not to study the animals’ natural life, but rather how to manipulate them to demonstrate ‘the possibility of re-creating man himself in the image of a generally acceptable ideal’- who would neatly fill the allocated slot in society.

Haraway talks about how between the First World War and the 1990s, the focus shifted from psychobiology to sociobiology, from organism to systems, from human engineering to population control. Systems design strives for optimization, not the perfection of the individual. And she posits that sociobiology is the science of capitalism, and science’s constructs have followed its metaphors- marriage as market exchange, cooperation as a management problem, altruism as a self-destructing behavior, scarcity and competition as the basis. So, is a feminist-socialist science possible, she asks. Not before we realize our social constructs are capitalist and patriarchal in essence, and not before we attempt at creating an alternative myth to explain it all. Feminism she says, is in part, a project for the reconstruction of public life and public meanings, a search for creating a myth about life, similar to what science does.

One difficulty lies in the plethora of scientific study/constructs that have been done until recently, most with a male-bias, under patriarchy’s light. This inheritance of ‘knowledge’ is making it so difficult to come up with alternative narratives that she says: ‘[Gender] is an unavoidable condition of observation. So also are class, race and nation’. Yet, she moves on: ‘Despite important differences, all the modern feminist meanings of gender have roots in Simon de Beauvoir’s claim that ‘one is not born a woman’.

Mentioning R. Stoller’s concept of gender identity in the 1960s formulated as sex being related to biology, and gender being related to culture, she asserts that obligatory heterosexuality is central to the oppression of women. Gayle Rubin: ‘If the sexual property system were reorganized in such a way that men did not have overriding rights in women [and] if there were no gender, the entire Oedipal drama would be a relic. In short, feminism must call for a revolution in kinship’ (1975).

Haraway describes her Cyborg Manifesto that follows as ‘an effort to build an ironic political myth faithful to feminism, socialism and materialism’. ‘Irony is about contradictions that do not resolve into larger wholes, even dialectically, about the tension of holding incompatible things together because both or all are necessary and true’. With the 20th century, the distinctions between human and animal, human/animal and machine, physical and non-physical have become ambiguous, she says. Therefore we can imagine a cyborgian existence with partial identities and contradictory standpoints. ‘It is the simultaneity of breakdowns that cracks the matrices of domination and opens geometric possibilities’. ‘Cyborg imagery can suggest a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves. This is a dream not of a common language, but of a powerful infidel heteroglossia’.

‘Every story that begins with original innocence and privileges the return to wholeness imagines the drama of life to be individuation, separation, the birth of the self, the tragedy of autonomy, the fall into writing, alienation, that is, war, tempered by imaginary respite in the bosom of the Other. These plots are ruled by reproductive politics’.

This I found to be a powerful attempt at handling the enormous task of finding oneself mired in overwhelming history, and braving a new myth. She proposes regeneration instead of rebirth. Possible easy criticism could be about the quick eagerness and enthusiasm of embracing the new technologies at the time, and also about remaining too much in theory land, and also about the negative connotations of an ironic approach. Yet ’embracing’ as an alternative to be explored seems more restoring compared to stale readings of power and domination.

The next chapter is about partial perspectives promising objective vision. ‘The only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere particular’. She says being everywhere and nowhere as in relativism denies responsibility and escapes criticism. Boundaries materialize with social interaction or with mapping practices, but boundaries shift and are fluid she says, and with this imperfect stitching together of realities we can join with others without claiming to be another.

(Source: www.wikipedia.org)

On self and other, differences, and the immune system discourse: ‘[The] immune system is a plan for meaningful action to construct and maintain the boundaries for what may count as self and other in the crucial realms of the normal and the pathalogical’- a highly militarized construct of science. Sex and reproduction are constructed as investment strategies; diseases are seen as malfunctions of the ‘system’ or problems arising at the boundaries. Haraway reminds once again, ‘one is not born an organism’, that is a construct. And what counts as a unit, a one is highly problematic, ‘Individuality is a strategic defense problem’. Haraway stresses that all this does not mean therapeutic action should be denied, but a new perspective could be beneficial where we don’t think in terms of impermeable boundaries. Context is co-structure, co-text, and not simply surrounding information.

Haraway further explores Niels Jerne’s network theory in immunology where ‘self’ and ‘other’ become fluid. In this theory, the immune system is able to regulate itself by only using itself- molecules are able to act both as antibodies, and are also able to mirror antigens for the production of antibodies. There is no passive waiting for invasion. ‘In a sense, there could be no exterior antigenic structure, no ‘invader’ that the immune system had not already ‘seen’ and mirrored internally. ‘Self’ and ‘other’ lose their rationalistic oppositional quality and become subtle plays of partially mirrored readings and responses.’ Haraway also questions what is perceived as invasion, giving the example of how the colonized people were perceived as the invader and threat to white people.

As sober as she remains all through the book (despite remaining mostly theoretical), she says ‘[The] world for us may be thoroughly denatured, but it is not any less consequential’. ‘When is a self enough of a self that its boundaries become central to entire institutionalized discourses in medicine, war and business?’.

The text is dense as Haraway has an interdisciplinary approach, making allusions to a myriad of contexts all the time, and I huffed and puffed my way through, until I got used to her style of writing. Having finished the book, I do not understand why my notes from the first half of the book say her writing feels like an assault on the art of writing, and it is as if she is taking private revenge from words, attacking and teasing with irony and sadistic intent. Yet, a year after reading the book, it remains in my memory as one of the better books I’ve read. I was also pleasantly surprised to not find a complaining victim perspective, and instead, to even find a bold attempt on the path to solving one monster of a problem- pun intended.

Her suggestion for the blurring of identities have been criticized for creating probable problems in human rights and social justice. Probably so, yet new and ‘original’ ideas usually take time to settle if will not be lost in the depths of history (to be excavated later?). As she emphasizes, her suggestions are not meant as a perfect, polished and packaged solution, and neither do they need to be.

FURTHER READING:

ON SOCIAL FEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Socialist feminists highlight how motherhood and the gendered division of labor grows ‘naturally’ from women’s role as mothers, is the source of women’s exclusion from the public sphere, and creates women’s economic dependence on men. They assert that there is nothing natural about the gendered division of labor and show that the expectation that women perform all or most of reproductive labor, i.e. labor associated with birthing and raising children but also the cleaning, cooking, and other tasks necessary to support human life, deny women the capacity to participate fully in economic activity outside the home. In order to free themselves from the conditions of work as a mother and housekeeper, socialist feminists such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman saw the professionalization of housework as key.’

‘Perkins Gilman also recommended the redesign of homes in ways that would maximize their potential for creativity and leisure for women as well as men, i.e. emphasizing the need for rooms like studios and studies and eliminating kitchens and dining rooms. These changes would necessitate the communalization of meal preparation and consumption outside the home and free women from their burden of providing meals on a house-by-house scale.’

ON FEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal and social equality of the sexes.’

‘Although feminist advocacy is, and has been, mainly focused on women’s rights, some argue for the inclusion of men’s liberation within its aims, because they believe that men are also harmed by traditional gender roles.’

‘Mary Wollstonecraft is seen by many as a founder of feminism due to her 1792 book titled A Vindication of the Rights of Women in which she argues that class and private property are the basis of discrimination against women, and that women as much as men needed equal rights.’

‘The history of the modern western feminist movement is divided into multiple ‘waves’: The first comprised women’s suffrage movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries, promoting women’s right to vote [focus was on women’s political power, as opposed to de facto unofficial inequalities]. The second wave, the women’s liberation movement, began in the 1960s and campaigned for legal and social equality for women. In or around 1992, a third wave was identified, characterized by a focus on individuality and diversity. Additionally, some have argued for the existence of a fourth wave, starting around 2012, which has used social media to combat sexual harrassment, violence against women and rape culture; it is best known for the Me too movement.’

Criticism circled around these topics:

-No intersectional perspective

-Gender not thought of as a social construct

-To be a woman meant having it through biology/sex

-Didn’t consider or fight for non-white women

-Male-centric- made in the form of the way men see women

-Lacked the sexual freedom men had and women couldn’t

‘During the baby boom period feminism waned in importance. World wars had seen the provisional emancipation of some women, but post-war periods signalled the return to conservative roles.’

‘Simon de Beauvoir provided a Marxist solution, and an existential view on many of the questions of feminism with her ‘The Second Sex’ book in 1949. The book expressed feminists’ sense of injustice.’

‘Second-wave feminists see women’s cultural and political inequalities as inextricably linked and encourage women to understand aspects of their personal lives as deeply politicized and as reflecting sexist power structures.’

‘In 1963, Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique heped voice the discontent that American women felt. The book is widely credited with sparking the beginning of second-wave feminism in the United States. Within ten years, women made up over half the First World workforce.’

‘Third-wave feminism is traced to the emergence of the riot grrrl feminist punk subculture in Olympia, Washington, in the early 1990s, and to Anita Hill’s televised testimony in 1991- to an all-male, all-white Senate Judiciary Committee- that Clarence Thomas, nominated for the Supreme Court of the United States, had sexually harrassed her.’

‘Third-wave feminism also sought to challenge or avoid what it deemed the second-wave’s essentialist definitions of femininity, which, third-wave feminists argued, overemphasized the experiences of upper middle-class white women.

ON FEMINIST MOVEMENTS AND IDEOLOGIES (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Many overlapping feminist movements and ideologies have developed over the years. Feminism is often divided into three main traditions called liberal, radical, and socialist/Marxist feminism, sometimes known as the ‘Big Three’ schools of feminist thought. Since the late 20th century, newer forms of feminisms have also emerged. Some branches of feminism track the political leanings of the larger society to a greater or lesser degree, or focus on specific topics, such as the environment.’

ON LIBERAL FEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Liberal feminism, also known under other names such as reformist, mainstream, or historically as bourgeois feminism, arose from 19th-century first-wave feminism, and was historically linked to 19th-century liberalism and progressivism, while 19th-century conservatives tended to oppose feminism as such. Liberal feminism seeks equality of men and women through political and legal reform within a liberal democratic framework, without radically altering the structure of society; liberal feminism “works within the structure of mainstream society to integrate women into that structure”. During the 19th and early 20th centuries liberal feminism focused especially on women’s suffrage and access to education. Former Norwegian supreme court justice and former president of the liberal Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights, Karin Maria Bruzelius, has described liberal feminism as “a realistic, sober, practical feminism”.

Susan Wendell argues that “liberal feminism is a historical tradition that grew out of liberalism, as can be seen very clearly in the work of such feminists as Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill, but feminists who took principles from that tradition have developed analyses and goals that go far beyond those of 18th and 19th century liberal feminists, and many feminists who have goals and strategies identified as liberal feminist … reject major components of liberalism” in a modern or party-political sense; she highlights “equality of opportunity” as a defining feature of liberal feminism.

Liberal feminism is a very broad term that encompasses many, often diverging modern branches and a variety of feminist and general political perspectives; some historically liberal branches are equality feminism, social feminism, equity feminism, difference feminism, individualist/libertarian feminism, and some forms of state feminism, particularly the state feminism of the Nordic countries. The broad field of liberal feminism is sometimes confused with the more recent and smaller branch known as libertarian feminism, which tends to diverge significantly from mainstream liberal feminism. For example, “libertarian feminism does not require social measures to reduce material inequality; in fact, it opposes such measures … in contrast, liberal feminism may support such requirements and egalitarian versions of feminism insist on them.”

Catherine Rottenberg notes that the raison d’être of classic liberal feminism was “to pose an immanent critique of liberalism, revealing the gendered exclusions within liberal democracy’s proclamation of universal equality, particularly with respect to the law, institutional access, and the full incorporation of women into the public sphere.” Rottenberg contrasts classic liberal feminism with modern neoliberal feminism, which “seems perfectly in sync with the evolving neoliberal order.” According to Zhang and Rios, “liberal feminism tends to be adopted by ‘mainstream’ (i.e., middle-class) women who do not disagree with the current social structure.” They found that liberal feminism with its focus on equality is viewed as the dominant and “default” form of feminism.

ON RADICAL FEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Radical feminism arose from the radical wing of second-wave feminism and calls for a radical reordering of society to eliminate male supremacy. It considers the male-controlled capitalist hierarchy as the defining feature of women’s oppression and the total uprooting and reconstruction of society as necessary. Separatist feminism does not support heterosexual relationships. Lesbian feminism is thus closely related. Other feminists criticize separatist feminism as sexist.’

ON FEMINIST SEPARATISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Feminist separatism or separatist feminism is the theory that feminist opposition to patriarchy can be achieved through women’s sex segregation from men. Much of the theorizing is based in lesbian feminism.

Author Marilyn Frye describes feminist separatism as ‘separation of various sorts of modes from men and from institutions, relationships, roles and activities that are male-defined, male-dominated, and operating for the benefit of males and the maintenance of male privilege- this separation being initiated or maintained, at will, by women.’

‘Lesbian and feminist separatism have inspired the creation of art and culture reflective of its visions of female-centered societies. An important and sustaining aspect of lesbian separatism was the building of alternative community through ‘creating organizations, institutions and social spaces… women’s bookstores, restaurants, publishing collectives, and softball leagues fostered a flourishing lesbian culture.’

ON MATERIALIST IDEOLOGIES (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Rosemary Hennessy and Chrys Ingraham say that materialist forms of feminism grew out of Western Marxist thought and have inspired a number of different (but overlapping) movements, all of which are involved in a critique of capitalism and are focused on ideology’s relationship to women. Marxist feminism argues that capitalism is the root cause of women’s oppression, and that discrimination against women in domestic life and employment is an effect of capitalist ideologies. Socialist feminism distinguishes itself from Marxist feminism by arguing that women’s liberation can only be achieved by working to end both the economic and cultural sources of women’s oppression. Anarcha-feminists believe that class struggle and anarchyagainst the state require struggling against patriarchy, which comes from involuntary hierarchy.’

ON ECOFEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Ecofeminists see men’s control of land as responsible for the oppression of women and destruction of the natural environment. Ecofeminism has been criticized for focusing too much on a mystical connection between women and nature.’

ON STANDPOINT FEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Standpoint feminism is a theory that feminist social science should be practiced from the standpoint of women or particular groups of women, as some scholars (e.g. Patricia Hill Collins and Dorothy Smith) say that they are better equipped to understand some aspects of the world. A feminist or women’s standpoint epistomology proposes to make women’s experiences the point of departure, in addition to, and sometimes instead of men’s.’

‘This perspective argues that research and theory treat women and the feminist movement as insignificant and refuses to see traditional science as unbiased.’

ON FOURTH-WAVE FEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Fourth-wave feminism is a proposed extension of third-wave feminism which corresponds to a resurgence in interest in feminism beginning around 2012 and associated with the use of social media. According to feminist scholar Prudence Chamberlain’, the focus of the fourth wave is justice for women and opposition to sexual harrassment and violence against women. Its essence, she writes, is ‘incredulity that certain attitudes can still exist.’

ON SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONIST IDEOLOGIES (notes from Wikipedia.org):

In the late 20th century various feminists began to argue that gender roles are socially constructed, and that it is impossible to generalize women’s experiences across cultures and histories. Post-structural feminism draws on the philosophies of post-structuralism and deconstruction in order to argue that the concept of gender is created socially and culturally through discourse. Postmodern feminists also emphasize the social construction of gender and the discursive nature of reality; however, as Pamela Abbott et al. write, a postmodern approach to feminism highlights “the existence of multiple truths (rather than simply men and women’s standpoints)”.

ON POSTFEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

Postfeminism (alternatively rendered as post-feminism) is an alleged decrease in popular support for feminism from the 1990s onwards.’

‘Research conducted at Kent State University in the 2000s narrowed postfeminism to four main claims: support for feminism declined; women began hating feminism and feminists; society had already attained social equality, thus making feminism outdated; and the label ‘feminist’ has a negative stigma.’

ON INTERSECTIONALITY (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how groups’ and individuals’ social and political identities result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege. Examples of these intersecting and overlapping factors include gender, caste, sex, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, religion, disability, physical appearance, and age. These factors can lead to both empowerment and oppression.

An intersectional analysis considers a collection of factors that affect a social individual in combination, rather than considering each factor in [isolation].

Intersectionality arose in reaction to both white feminism and the then-male dominated black liberation movement, citing the ‘interlocking oppressions’ of racism, sexism and heteronormativity. It broadens the scope of the first and second waves of feminism, which largely focused on the experiences of women who were white, cisgender, and middle-class, to include the different experiences of women of color, poor women, immigrant women, and other groups, and aims to separate itself from white feminism by acknowledging women’s differing experiences and identities.’

ON WOMANISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Womanism is a feminist movement, primarily championed by Black feminists, originating in the work of African American author Alice Walker in her 1983 book In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens.’ ‘Walker defined ‘womanism’ as embracing the courage, audacity, and self-assured demeanor of Black women, alongside their love for other women, themselves, and all of humanity. Since its inception by Walker, womanism has expanded to encompass various domains, giving rise to concepts such as Africana womanism and womanist theology or spirituality.’

‘Womanism supports the idea that the culture of the woman, which in this case is the focal point of intersection as opposed to class or some other characteristic, is not an element of her identity but rather is the lens through which her identity exists. As such, a woman’s Blackness is not a component of her feminism. Instead, her Blackness is the lens through which she understands her feminist/womanist identity.’

‘[According to Alice Walker] a womanist is committed to the survival of both males and females and desires a world where men and women can coexist, while maintaining their cultural distinctiveness. This inclusion of men provides Black women with an opportunity to address gender oppression without directly attacking men.’

ON LIPSTICK FEMINISM

Lipstick feminism asserts that women can still be feminists and use make-up, ‘sexy’ clothing and such. There is criticism for that, too- is that really women expressing their free choice or is it rather submitting to sex-objectifying- their culturally conditioned self wanting to use lipstick for expression of self? Some also mention they are valid means to use for self-empowerment, but to me that just circles back to the debate of who is going to dominate who?

ON SECULAR HUMANISM AND FEMINISM (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Secular humanism is an ethical framework that attempts to dispense with any unreasoned dogma, pseudoscience, and superstition. Critics of feminism sometimes ask “Why feminism and not humanism?”. Some humanists argue, however, that the goals of feminists and humanists largely overlap, and the distinction is only in motivation.

ON GAYLE RUBIN (notes from Wikipedia.org):

‘Gayle S. Rubin (born January 1, 1949) is an American cultural anthropologist, theorist and activist, best known for her pioneering work in feminist theory and queer studies.’

‘In [‘The Traffic in Women:Notes on the Political Economy of Sex’], Rubin devised the phrase “sex/gender system”, which she defines as “the set of arrangements by which a society transforms biological sexuality into products of human activity, and in which these transformed sexual needs are satisfied.”

‘ She argues that the reproduction of labor power depends upon women’s housework to transform commodities into sustenance for the worker. The system of capitalism cannot generate surplus without women, yet society does not grant women access to the resulting capital.’

‘According to Rubin, “Gender is a socially imposed division of the sexes.” She cites the exchange of women within patriarchal societies as perpetuating the pattern of female oppression, referencing Marcel Mauss’ Essay on the Giftand using his idea of the “gift” to establish the notion that gender is created within this exchange of women by men in a kinshipsystem. Women are born biologically female, but only become gendered when the distinction between male giver and female gift is made within this exchange. For men, giving the gift of a daughter or a sister to another man for the purpose of matrimony allows for the formation of kinship ties between two men and the transfer of “sexual access, genealogical statuses, lineage names and ancestors, rights and people” to occur. When using a Marxist analysis of capitalism within this sex/gender system, the exclusion of women from the system of exchange establishes men as the capitalists and women as their commodities fit for exchange. She ultimately argues that, in the current moment, a genderless identity and a polymorphous sexuality with no hierarchies are possible if we break away from the “now functionless” sex/gender system.’

‘[It] is a striking fact that the formal theory of nature embodied in sociobiology is structurally like advanced capitalist theories of investment management, control systems for labor, and insurance practices based on population disciplines.’

‘Nature can be lazy, and seems to have abondoned a natural theological project of adoptive perfection.’

‘Nature is, above all, profligate.. (Its schemes) are the brainchild of a deranged manic-depressive with limitless capital. Extravagance. Nature will try anything once. …[No] form is too gruesome, no behavior too grotesque. …[This] is a spendthrift economy; though nothing is lost, all is spent.’ Annie Dillard

‘In difference is the irretrievable loss of the illusion of the one.’

‘Monsters have always defined the limits of community in Western imaginations. Centaurs and Amazons of amcient Greece established the limits of the cenred polis of the Greek male human by their disruption of marriage and boundary pollutions of the warrior with animality and women.’

Author: Donna Haraway

Title: Simians, Cyborgs and Women / The Reinvention of Nature

Published: 1991, by Free Association Books

First published: 1991

Pages: 287