TIME OF THE ASSASSINS

(Source: www.amazon.com.tr)

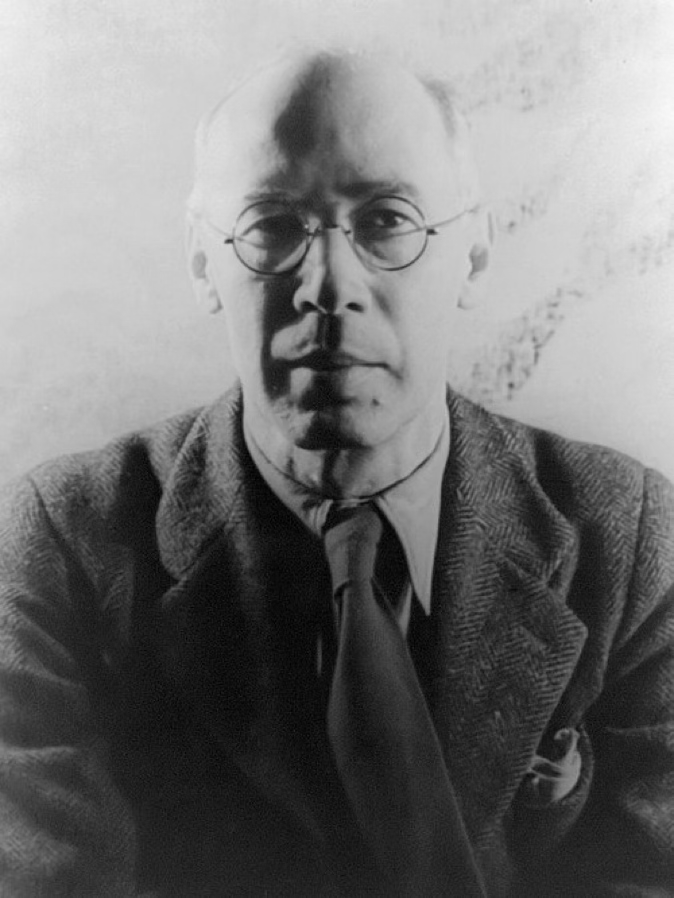

Henry Miller (1891-1980) was an American author who also painted around 2000 watercolors, as well as writing about them. His mostly autobiographical novels which included ample sexual content made him a liberating influence at the time, although most of his fame came later in his life.

In 1924 Miller left his personnel management job, divorced his first wife and married June Mansfield who become a major inspiration for his works. Jean Kronski lived with them for some time who Miller suspected to be having an affair with June. In 1930 Miller moved to Paris, met Anais Nin who would also become his lover, muse and financial supporter (along with her husband). June was also entangled in their relationship, and both Miller’s and Nin’s work seem to be heavily cronicling their private lives. Miller also befriended Lawrence Durrell at this time, and their correspondence was later published. The three novels that he wrote around this time went unpublished for over 60 years.

Miller’s 1934 Tropic of Cancer had explicit sexual passages which resulted in its ban in the US. Copies of its French publication were smuggled to the US, and when it was finally printed in 1961, many booksellers were sued.

The Supreme Court’s 1964 overruling of the findings of obscenity in the work, and declaring it a work of literature was one of the cornerstones of the second sexual revolution in the 1960s.

Miller moved to California in 1940 as his smuggled books were becoming a major influence on the Beat Generation. His life from then on continued along the same vein, he kept authoring books, and marrying women. In the last four years of his life, he corresponded as a pen pal with Brenda Venus to whom he wrote around 4000 pages which were published in 1986. A capricorn.

Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891) was a French poet who stopped poeting at age 20, after which he traveled extensively as a merchant and explorer until his death. He rejected the naturalism and realism of his time, and believed in the purpose of art as being beyond the representation of reality, towards reaching higher truths through the ‘systematic derangement of the senses’.

Rimbaud was the second of the five children in the family, and his father was continually absent while on military postings. His mother is described as narrowminded, stingy and humorless, contrasting his husband’s character. After the couple’s separation around 1860, neither him nor the children made any attempt for contact.

Rimbaud resented his authoritarian mother’s strict supervision, and from very early on, saw schoolwork as only leading to a salaried position, and aspired for a different life, while also being highly successful in school. In 1870 he ran away to Paris where he managed to stay with the help of a former teacher. There he transformed into a drinking, drugging, stealing, rude person, disheveled in appearance. After a tumultous romance with poet Paul Verlaine, Verlaine shot Rimbaud in the wrist, and Rimbaud returned home and wrote ‘A Season in Hell’. In 1874 he went to London with poet G. Nouveau, and wrote ‘Illuminations’ in three months.

After extensive travels, in 1884, he became a merchant dealing mainly in coffee and firearms in Ethiopia. In 1891, a problem with his knee led to the amputation of his leg in France. His last days were accompanied by his sister Isabelle. A libra.

Miller’s study of Rimbaud is not a conventional literary criticism, but a totally subjective exploration of the role of an artist in society. It does not dwell in, but around and beyond Rimbaud’s life and work, embracing the light and the dark.

Miller says the leading poets of the 19th and 20th centuries had a prophetic strain which the contemporary ones are lacking, and they are writing with a cryptic language which to him is gibberish. The poet no longer believes in his divine mission. And art, when only ‘understood’ by a select few, is no longer art, but ‘the cipher language of a secret society for the propagation of meaningless individuality’. He says we now have knowledge without wisdom, comfort without security, belief without faith, and the poetry of life is explained in mathematical, physical, chemical terms, and the poet is an anomaly on his way to extinction. ‘[Poets] are always announcing the advent of things to come and we crucify them because we live in dread of the unknown. In the poet the springs of action are hidden’. He says these come clothed in secrecy and mystery, but there is a vast difference between ‘the use of a more symbolic script and the use of a more highly personal jargon which I referred to as ‘gibberish”.

(Source: www.amazon.com.tr)

‘At the periphery the world is dying away; at the center it glows like a live coal. The brotherhood of man consists not in thinking alike, nor in acting alike, but in aspiring to praise creation. The song of creation springs from the ruins of earthly endeavor. The outer man dies away in order to reveal the golden bird which is winging its way toward divinity’.

Rimbaud is often blamed for abandoning ‘the cause’ by leaving poetry behind in search of material wealth. I believe, many times people overlook the fact that he died young, and there is no indication that he did not intend to go back to it. Maybe he considered that life as part of the ‘systematic derangement of the senses’, but it was cut short. There are countless examples in artists’ lives of what I call silent retreats for a myriad of reasons, and many of which are oddly disguised in biographies. Miller says ‘he was cheated of that final phase of development which permits a man to harmonize his warring selves’. He says all rebels are really rebelling to free from the mother, be an individual and unite with the rest of mankind, and unless they do, they feel alone and isolated just like Rimbaud. He attributes Rimbaud’s rebellious nature also to the matrix his parents’ clash created. Yet Miller adds sarcastically that solidarity is a myth at this age: ‘Solidarity is for slaves who wait until the world becomes one huge wolf pack.. Then they will pounce all at once, all together, and rip and rend like envious beasts’. And Rimbaud is a lone wolf.

Miller questions whether the mission of youth really is to combat the errors of the ancestors, rebel, destroy, assassinate: ‘Stifle or deform youth’s dreams and you destroy the creator. Where there has been no real youth there can be no real manhood’.

Miller also likens Rimbaud’s silent period to the technique of a sage- with maintaining a resolute silence he asserts his presence/ his poetry stronger.

‘[The] task of the future is to explore the domain of evil until not a shred of mystery is left. We shall discover the bitter roots of beauty, accept root and flower, leaf and bud. We can no longer resist evil: we must accept’. And again, Rimbaud’s second half of his life was maybe shaped to that end.

Miller says our world is made up of dualities where the poet clarifies which is what, embraces all, and guides the way, and the ones in the confusion of the twilight zone where it is not clear what the light and what the darkness is, live in a death valley where assassins reign. For him, Rimbaud might be in that valley because he left his divine mission behind because he thought he could find his freedom outside himself, in financial security. The strength of the rebel, the evil one, comes from its obstinance about his egotistical needs, which leads to isolation, while true strength lies in submitting for the greater good which results in unification with mankind, and therefore fertility and creation.

‘Death lies in separation, in living apart. It does not mean simply to cease being’- echoing Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo from another angle.

‘[All the great spirits of the modern age] were like inventors who, having discovered electricity, knew nothing about insulation’.

‘I think the Rimbaud type will displace, in the world to come, the Hamlet type and the Faustian type. [Until] the old world dies out utterly, the ‘abnormal’ individual will tend more and more to become the norm. The new man will find himself only when the warfare between the collectivity and the individual ceases. Then we shall see the human type in its fullness and splendor.’

‘God wrote the score, God constructs the orchestra. Man’s role is to make music with his own body. Heavenly music, [for] all else is cacaphony.’

‘[The] task of the future is to explore the domain of evil until not a shred of mystery is left. We shall discover the bitter roots of beauty, accept root and flower, leaf and bud. We can no longer resist evil: we must accept.’

‘[All the great spirits of the modern age] were like inventors who, having discovered electricity, knew nothing about insulation’.

Author: Henry Miller

Title: The Time of the Assassins / A Study of Rimbaud

Published: 1962, by New Directions

First published: 1946

Pages: 163